Reflections

9/6/2018

For as long as I can remember, I’ve had an affinity for “Native American Culture.” As a child, I was drawn to something I did not (and still do not) completely understand. I’m not even exactly sure what it was back then that pulled at my soul. I’d like to think it was an understanding that Indians had a deep-seated love of nature, except that as a child I didn’t really fully understand that I even had an inherent love of nature myself. Perhaps it was the depiction of the Indian understanding of animals as beings with spirit. I think I got that about myself then, that I had that same understanding. Whatever the reason, my attraction to this idea, this mythology, of Native Americans was without an understanding of the reality. We like to lump Native Americans under one nice and tidy label that is somehow supposed to sum up the numerous cultures and histories of tribes that currently and historically inhabited North America. Whether we identify the Indian, or Native American, as savage or as the bearer of wisdom, our label allows us to neatly categorize and compartmentalize many tribes of people with their rich and deep histories and their presents. It allows us to gloss over the realities of the lives of people. Real people. People who love, laugh, learn, make mistakes both great and small. Who have great strengths and great weaknesses. And, yes, who have cultures, beliefs, and traditions that continue to thread through modern lives.

We recently visited the Crazy Horse Memorial. I REALLY wanted to see this memorial. You see, in addition to this great attraction I have, I have an equally great feeling of guilt and sadness over what we have done (and continue to do) to those we conquered. Because, while our family lore has always identified us as part Native American, that doesn’t excuse my mostly European ancestors from participating, even if indirectly, in the decimation of countless men, women, and children who were here long before us. So, I had been excited to see this symbol that is being constructed to honor the Native American tribes in South Dakota (and across North America). I was wholly unprepared for the reaction I had upon walking around the museum, grounds, and gift shop.

Conflicted. Gut-wrenching sorrow. Honored. Doubt. Curiosity. They were all there, taking turns rolling through heart and mind, each staking it’s claim on my conscience, each vying for prominence. It was a busy day, with tourists meandering through the museum, briefly glancing at the artifacts and photographs on their way to the gift shop or out into the courtyard to watch a Lakota family play traditional music, dance, provide a brief synopsis of some tribal traditions, and invite everyone to hold hands and move in a friendship circle. The words and the song we heard of the husband and wife were beautiful and moving. They held out the hope of peace, friendship, and understanding. I was moved to tears, while also wanting to cry because I had to wonder: what is it these tourists are here for and what are they getting from this experience? For how many is it just spectacle and entertainment? A check mark of “things to do” on a tour of the Black Hills? How many feel the tug at their hearts of the hope in the words and music of this family who is willing to share a bit of themselves? How many are curious to know more of the story? To know what other experiences embody the life and traditions of this modern Lakota family? I myself had so many questions, so much more I wanted to know about what else holds true for this family and why they put themselves out there for tourists to see and what else do they dream for the future of their family, their tribe, the nation, and the world? But I kept quiet, even when I saw them in the restaurant afterwards. I was too afraid to be intrusive and too afraid my motives would be misunderstood.

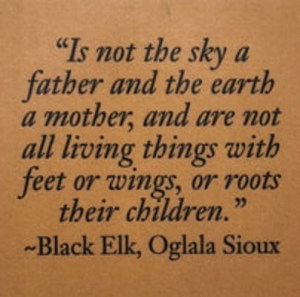

I still feel an affinity for “Native American Culture.” Yes, perhaps somewhat for the mythology, but, I think too for at least some of what I understand to be a common thread of love and respect for the natural world around us, for the understanding that we, as humans, are all a part of this natural world, not apart from and above it. But I feel that the connection is more than that. Perhaps it can be chalked up to empathy as well as admiration. For the endurance and strength of people who have been beaten down for centuries now and, yet, they carry on. Whatever the connection is, I can still say that it is for a way of living that I still do not, and will not ever, fully understand because I do not walk in their shoes. But I can sure try.

Peace.

Desserae